Reading <Types & Grammar> - 2

Chapter 4: Coercion

Converting Values

Converting a value from one type to another is often called “type casting,” when done explicitly, and “coercion” when done implicitly (forced by the rules of how a value is used).

显式类型转换和隐式类型转换对应的英文。

The terms “explicit” and “implicit,” or “obvious” and “hidden side effect,” are relative.

If you know exactly what

a + ""is doing and you’re intentionally doing that to coerce to astring, you might feel the operation is sufficiently “explicit.” Conversely, if you’ve never seen theString(..)function used forstringcoercion, its behavior might seem hidden enough as to feel “implicit” to you.

这段挺有意思,即隐式或显式是相对的,即一个人如果对某种方式进行的类型转换非常熟悉,那么这种方式对于他来说就是显示的,反之亦然。

当然这有一些诡辩的感觉,毕竟你写的代码不是只有你一个人看的,那么可以认为大多数人熟悉的类型转换方式为显式,否则为隐式比较合适。

Abstract Value Operations

The

JSON.stringify(..)utility will automatically omitundefined,function, andsymbolvalues when it comes across them. If such a value is found in anarray, that value is replaced bynull(so that the array position information isn’t altered). If found as a property of anobject, that property will simply be excluded.Consider:

JSON.stringify( undefined ); // undefined JSON.stringify( function(){} ); // undefined JSON.stringify( [1,undefined,function(){},4] ); // "[1,null,null,4]" JSON.stringify( { a:2, b:function(){} } ); // "{"a":2}"

JSON.stringify(..)使用注意事项1。此外,如果函数对象拥有toJSON方法,则序列化时会使用这个方法的返回值,而不是undefined或是被忽略了。(另一个角度,即toString、toJSON这类方法可以看作是这些JavaScript标准库提供的对应的hook,方便其他代码更好地适用于标准库方法。)

An optional second argument can be passed to

JSON.stringify(..)that is called replacer. This argument can either be anarrayor afunction. It’s used to customize the recursive serialization of anobjectby providing a filtering mechanism for which properties should and should not be included, in a similar way to howtoJSON()can prepare a value for serialization.var a = { b: 42, c: "42", d: [1,2,3] }; JSON.stringify( a, ["b","c"] ); // "{"b":42,"c":"42"}" JSON.stringify( a, function(k,v){ if (k !== "c") return v; } ); // "{"b":42,"d":[1,2,3]}"Note: In the

functionreplacer case, the key argumentkisundefinedfor the first call (where theaobject itself is being passed in). Theifstatement filters out the property named"c". Stringification is recursive, so the[1,2,3]array has each of its values (1,2, and3) passed asvto replacer, with indexes (0,1, and2) ask.

JSON.stringify(..)使用注意事项2。即可以传递一个array或函数来过滤序列化的输出结果,注意JSON序列化是一个树状的结构,所以过滤应用的对象是树的每一个节点。

If any non-

numbervalue is used in a way that requires it to be anumber, such as a mathematical operation, the ES5 spec defines theToNumberabstract operation in section 9.3.For example,

truebecomes1andfalsebecomes0.undefinedbecomesNaN, but (curiously)nullbecomes0.

ToNumberfor astringvalue essentially works for the most part like the rules/syntax for numeric literals (see Chapter 3). If it fails, the result isNaN(instead of a syntax error as withnumberliterals).

注意这里的ToNumber是一个”abstract operation”,即真实世界是不存在这个函数的,可以理解为没公开的编译器内部的一个函数。非Object或array类型转换到number都是使用了它们的“ToNumber”操作。

Objects (and arrays) will first be converted to their primitive value equivalent, and the resulting value (if a primitive but not already a

number) is coerced to anumberaccording to theToNumberrules just mentioned.To convert to this primitive value equivalent, the

ToPrimitiveabstract operation (ES5 spec, section 9.1) will consult the value (using the internalDefaultValueoperation – ES5 spec, section 8.12.8) in question to see if it has avalueOf()method. IfvalueOf()is available and it returns a primitive value, that value is used for the coercion. If not, buttoString()is available, it will provide the value for the coercion.If neither operation can provide a primitive value, a

TypeErroris thrown.

Object和array类型转换到number会先调用它们的valueOf方法(如果没有则调用toString方法替代,再没有就抛异常),再把结果放到“ToNumber”操作中输出结果。

All of JavaScript’s values can be divided into two categories:

- values that will become

falseif coerced toboolean- everything else (which will obviously become

true

所以,只要记下面的falsy value就可以了,其他都是truthy value。(当然,作者还提到由于历史上某些公司的逆天行为,浏览器中存在某些特殊的Object是falsy的,真是谁强谁定规则啊。不过我们并不需要太在意这些edge case。)

From that table, we get the following as the so-called “falsy” values list:

undefinednullfalse+0,-0, andNaN""

What about these?

var a = []; // empty array -- truthy or falsy? var b = {}; // empty object -- truthy or falsy? var c = function(){}; // empty function -- truthy or falsy? var d = Boolean( a && b && c ); d;Yep, you guessed it,

dis stilltruehere. Why? Same reason as before. Despite what it may seem like,[],{}, andfunction(){}are not on the falsy list, and thus are truthy values.

熟悉Python的得习惯过来了。

Explicit Coercion

var a = 42; var b = a.toString(); var c = "3.14"; var d = +c; b; // "42" d; // 3.14Is

+cexplicit coercion? Depends on your experience and perspective. If you know (which you do, now!) that unary+is explicitly intended fornumbercoercion, then it’s pretty explicit and obvious. However, if you’ve never seen it before, it can seem awfully confusing, implicit, with hidden side effects, etc.Note: The generally accepted perspective in the open-source JS community is that unary

+is an accepted form of explicit coercion.

知道能通过添加一个+来转换成number就可以了。

Consider:

var a = "42"; var b = "42px"; Number( a ); // 42 parseInt( a ); // 42 Number( b ); // NaN parseInt( b ); // 42Parsing a numeric value out of a string is tolerant of non-numeric characters – it just stops parsing left-to-right when encountered – whereas coercion is not tolerant and fails resulting in the

NaNvalue.Parsing should not be seen as a substitute for coercion. These two tasks, while similar, have different purposes. Parse a

stringas anumberwhen you don’t know/care what other non-numeric characters there may be on the right-hand side. Coerce astring(to anumber) when the only acceptable values are numeric and something like"42px"should be rejected as anumber.

parseInt会从左向右解析输入的string(如果不是string会被先转换成string),直到不能解析为止,返回之前能解析的部分作为结果。

Some would argue that this is unreasonable behavior, and that

parseInt(..)should refuse to operate on a non-stringvalue. Should it perhaps throw an error? That would be very Java-like, frankly. I shudder at thinking JS should start throwing errors all over the place so thattry..catchis needed around almost every line.

作者认为JavaScript的特点之一是不会频繁地抛异常。(但比起产生一些难以发现的bug,要去catch异常也还好吧。。)

So, back to our

parseInt( 1/0, 19 )example. It’s essentiallyparseInt( "Infinity", 19 ). How does it parse? The first character is"I", which is value18in the silly base-19. The second character"n"is not in the valid set of numeric characters, and as such the parsing simply politely stops, just like when it ran across"p"in"42px".The result?

18. Exactly like it sensibly should be. The behaviors involved to get us there, and not to an error or toInfinityitself, are very important to JS, and should not be so easily discarded.Other examples of this behavior with

parseInt(..)that may be surprising but are quite sensible include:parseInt( 0.000008 ); // 0 ("0" from "0.000008") parseInt( 0.0000008 ); // 8 ("8" from "8e-7") parseInt( false, 16 ); // 250 ("fa" from "false") parseInt( parseInt, 16 ); // 15 ("f" from "function..") parseInt( "0x10" ); // 16 parseInt( "103", 2 ); // 2

考察基本功的来了。

Just like the unary

+operator coerces a value to anumber(see above), the unary!negate operator explicitly coerces a value to aboolean. The problem is that it also flips the value from truthy to falsy or vice versa. So, the most common way JS developers explicitly coerce tobooleanis to use the!!double-negate operator, because the second!will flip the parity back to the original:var a = "0"; var b = []; var c = {}; var d = ""; var e = 0; var f = null; var g; !!a; // true !!b; // true !!c; // true !!d; // false !!e; // false !!f; // false !!g; // false

前面添加!!是用来转换到布尔类型的。

Implicit Coercion

Let’s define the goal of implicit coercion as: to reduce verbosity, boilerplate, and/or unnecessary implementation detail that clutters up our code with noise that distracts from the more important intent.

Many developers believe that if a mechanism can do some useful thing A but can also be abused or misused to do some awful thing Z, then we should throw out that mechanism altogether, just to be safe.

My encouragement to you is: don’t settle for that. Don’t “throw the baby out with the bathwater.” Don’t assume implicit coercion is all bad because all you think you’ve ever seen is its “bad parts.” I think there are “good parts” here, and I want to help and inspire more of you to find and embrace them!

不能因噎废食。

Consider:

var a = [1,2]; var b = [3,4]; a + b; // "1,23,4"Neither of these operands is a

string, but clearly they were both coerced tostrings and then thestringconcatenation kicked in. So what’s really going on?

又是一个pythoner要注意的坑。至于为什么结果会是这样,其实和之前的ToNumber操作类似,先尝试转换成number,失败了再转换成string,再进行string的相加操作。

Consider:

var a = { valueOf: function() { return 42; }, toString: function() { return 4; } }; a + ""; // "42" String( a ); // "4"

很好地诠释了相加操作的隐式转换和显示转换的区别。

What about the other direction? How can we implicitly coerce from

stringtonumber?var a = "3.14"; var b = a - 0; b; // 3.14

因为减号是number特有的操作,string并没有重载这个操作符,所以减号两端的对象会被先转换成number再操作(即使转换失败了也是NaN,而不是抛异常,JavaScript果真是一个不喜欢抛异常的语言)。还有乘号和除号也可以达到一样的效果。(注意Python里面string的乘号是被重载了的!)

In fact, I would argue these operators shouldn’t even be called “logical ___ operators”, as that name is incomplete in describing what they do. If I were to give them a more accurate (if more clumsy) name, I’d call them “selector operators,” or more completely, “operand selector operators.”

Why? Because they don’t actually result in a logic value (aka

boolean) in JavaScript, as they do in some other languages.So what do they result in? They result in the value of one (and only one) of their two operands. In other words, they select one of the two operand’s values.

Let’s illustrate:

var a = 42; var b = "abc"; var c = null; a || b; // 42 a && b; // "abc" c || b; // "abc" c && b; // nullWait, what!? Think about that. In languages like C and PHP, those expressions result in true or false, but in JS (and Python and Ruby, for that matter!), the result comes from the values themselves.

第一次发现原来Python里面and、or这类操作符返回的也不是直接的布尔值。

Another way of thinking about these operators:

a || b; // roughly equivalent to: a ? a : b; a && b; // roughly equivalent to: a ? b : a;

Loose Equals vs. Strict Equals

A very common misconception about these two operators is: “

==checks values for equality and===checks both values and types for equality.” While that sounds nice and reasonable, it’s inaccurate. Countless well-respected JavaScript books and blogs have said exactly that, but unfortunately they’re all wrong.The correct description is: “

==allows coercion in the equality comparison and===disallows coercion.”

第一种说法的问题在于,无论是==还是===都是会检查两边的类型的,只是==在检查完类型之后会进行隐式类型转换(如果两边类型不同的话),而===则对于类型不同的情况直接就返回false了。

The final provision in clause 11.9.3.1 is for

==loose equality comparison withobjects (includingfunctions andarrays). Two such values are only equal if they are both references to the exact same value. No coercion occurs here.Note: The

===strict equality comparison is defined identically to 11.9.3.1, including the provision about twoobjectvalues. It’s a very little known fact that == and === behave identically in the case where twoobjects are being compared!

注意两个array的比较也是比较指针的(即相当于Python里面的is)!比如下面的例子:

var a = [1, 2, 3]

var b = [1, 2, 3]

a == b // false

Next, let’s consider another tricky example, which takes the evil from the previous example to another level:

if (a == 2 && a == 3) { // .. }You might think this would be impossible, because

acould never be equal to both2and3at the same time. But “at the same time” is inaccurate, since the first expressiona == 2happens strictly beforea == 3.So, what if we make

a.valueOf()have side effects each time it’s called, such that the first time it returns2and the second time it’s called it returns3? Pretty easy:var i = 2; Number.prototype.valueOf = function() { return i++; }; var a = new Number( 42 ); if (a == 2 && a == 3) { console.log( "Yep, this happened." ); }

这段很精彩,another trick。

The most important advice I can give you: examine your program and reason about what values can show up on either side of an

==comparison. To effectively avoid issues with such comparisons, here’s some heuristic rules to follow:

- If either side of the comparison can have

trueorfalsevalues, don’t ever, EVER use==.- If either side of the comparison can have

[],"", or0values, seriously consider not using==.In these scenarios, it’s almost certainly better to use

===instead of==, to avoid unwanted coercion. Follow those two simple rules and pretty much all the coercion gotchas that could reasonably hurt you will effectively be avoided.

如果要用==的话需要注意上面这两点,但我个人倾向于还是都用===吧(感觉作者全篇都在劝我们不要盲目相信coericon is evil,但我还是十动然拒)。

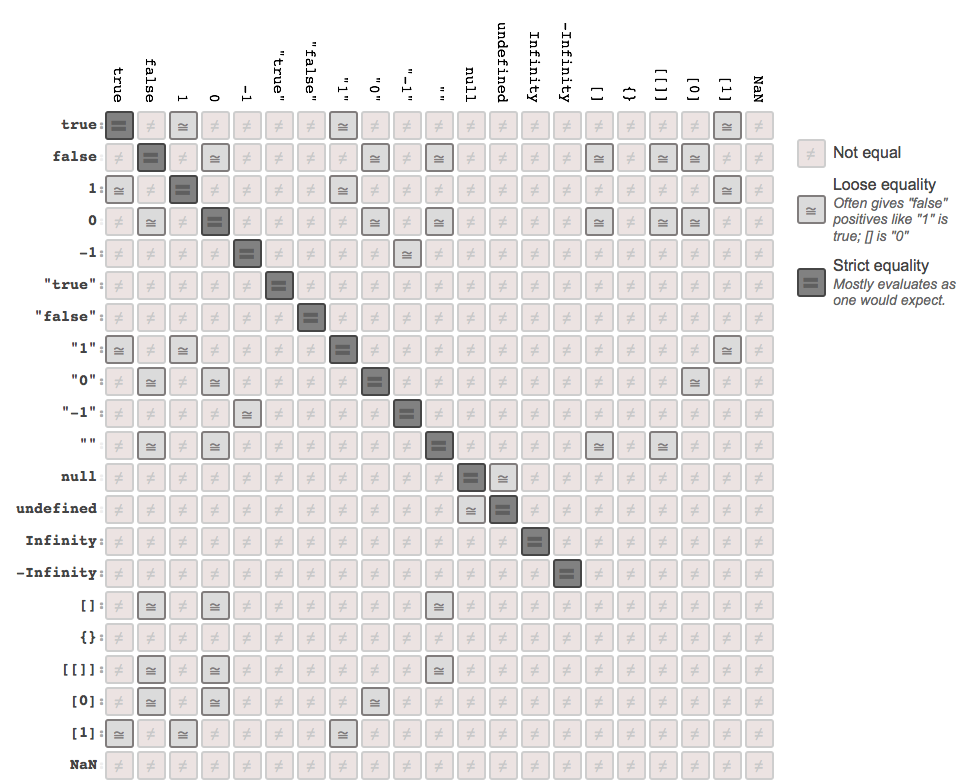

好图。

Abstract Relational Comparison

The algorithm first calls

ToPrimitivecoercion on both values, and if the return result of either call is not astring, then both values are coerced tonumbervalues using theToNumberoperation rules, and compared numerically.For example:

var a = [ 42 ]; var b = [ "43" ]; a < b; // true b < a; // falseNote: Similar caveats for

-0andNaNapply here as they did in the==algorithm discussed earlier.However, if both values are

strings for the<comparison, simple lexicographic (natural alphabetic) comparison on the characters is performed:var a = [ "42" ]; var b = [ "043" ]; a < b; // false

简单说就是先都进行ToPrimitive操作,如果两者都转换成了string,则进行字符比较,否则都转换成number进行数字比较。

由于不存在像===一样的“严格大于”或“严格小于”,所以还是不可避免的要接触到这些隐式转换的规则,所以上面关于==的一些建议也可以参考。

But strangely:

var a = { b: 42 }; var b = { b: 43 }; a < b; // false a == b; // false a > b; // false a <= b; // true a >= b; // trueWhy is

a == bnottrue? They’re the samestringvalue ("[object Object]"), so it seems they should be equal, right? Nope. Recall the previous discussion about how==works withobjectreferences.But then how are

a <= banda >= bresulting intrue, ifa < banda == banda > bare allfalse?Because the spec says for

a <= b, it will actually evaluateb < afirst, and then negate that result. Sinceb < ais alsofalse, the result ofa <= bistrue.

各种坑啊,所以尽量别用<=或>=吧(a <= b就用b < a代替)。

Comments