Reading <Async & Performance> - 1

Chapter 1: Asynchrony: Now & Later

Event Loop

So what is the event loop?

Let’s conceptualize it first through some fake-ish code:

// `eventLoop` is an array that acts as a queue (first-in, first-out) var eventLoop = [ ]; var event; // keep going "forever" while (true) { // perform a "tick" if (eventLoop.length > 0) { // get the next event in the queue event = eventLoop.shift(); // now, execute the next event try { event(); } catch (err) { reportError(err); } } }

It’s important to note that

setTimeout(..)doesn’t put your callback on the event loop queue. What it does is set up a timer; when the timer expires, the environment places your callback into the event loop, such that some future tick will pick it up and execute it.What if there are already 20 items in the event loop at that moment? Your callback waits. It gets in line behind the others – there’s not normally a path for preempting the queue and skipping ahead in line. This explains why

setTimeout(..)timers may not fire with perfect temporal accuracy. You’re guaranteed (roughly speaking) that your callback won’t fire before the time interval you specify, but it can happen at or after that time, depending on the state of the event queue.

setTimeout函数是在一定时间之后将回调函数插入到event loop之中,但其并不保证插入之后便立即得到执行(取决于插入时event loop队列是否为空,比如setTimeout(..., 0)并不会在该语句执行完后就立刻执行,而是会在当前整段代码执行完成之后再执行,比如下面的代码)。

setTimeout(function () {

console.log('A')

}, 0);

function demo() {

setTimeout(function () {

console.log('B');

}, 0);

console.log('C');

}

demo();

console.log('D');

最后输出的顺序是CDAB,即整块代码中同步的部分会先执行,然后再是异步的部分。或者这样理解,执行上面的代码块本身是一个是atomic task,两个setTimeout函数分别又创建了两个task,并安排在当前task执行完之后执行。

Because of JavaScript’s single-threading, the code inside of

foo()(andbar()) is atomic, which means that oncefoo()starts running, the entirety of its code will finish before any of the code inbar()can run, or vice versa. This is called “run-to-completion” behavior.

Javascript是单线程的,所以在一个瞬间只有一段代码会被执行。而由于event loop的机制,所有插入其中的task都自带了原子属性,即一个task完全执行完才会去执行下一个task,即使这两个task被安排到了同一时间执行也是如此(安排在同一时间就按照进入event loop的先后来按顺序执行呗)。有点Python中协程的感觉。

Concurrency

Cooperation

Here, the focus isn’t so much on interacting via value sharing in scopes (though that’s obviously still allowed!). The goal is to take a long-running “process” and break it up into steps or batches so that other concurrent “processes” have a chance to interleave their operations into the event loop queue.

For example, consider an Ajax response handler that needs to run through a long list of results to transform the values. We’ll use

Array#map(..)to keep the code shorter:var res = []; // `response(..)` receives array of results from the Ajax call function response(data) { // add onto existing `res` array res = res.concat( // make a new transformed array with all `data` values doubled data.map( function(val){ return val * 2; } ) ); } // ajax(..) is some arbitrary Ajax function given by a library ajax( "http://some.url.1", response ); ajax( "http://some.url.2", response );If

"http://some.url.1"gets its results back first, the entire list will be mapped intoresall at once. If it’s a few thousand or less records, this is not generally a big deal. But if it’s say 10 million records, that can take a while to run (several seconds on a powerful laptop, much longer on a mobile device, etc.).While such a “process” is running, nothing else in the page can happen, including no other

response(..)calls, no UI updates, not even user events like scrolling, typing, button clicking, and the like. That’s pretty painful.

解决方法就是把一个task拆分成多个:在response函数中先拆分data,最后调用setTimeout()新创建一个task来处理拆分下来的还没处理的那部分data(具体代码没贴,看原文)。这里的解决方法还是比较有启发性的,比如页面上面有两个分页的表格,使用这种方法就可以把两个表格的第一页内容先渲染出来,而如果不拆分的话,则第二张表格要等第一个表格完全渲染完成后才会开始渲染。

Jobs

As of ES6, there’s a new concept layered on top of the event loop queue, called the “Job queue.” The most likely exposure you’ll have to it is with the asynchronous behavior of Promises (see Chapter 3).

So, the best way to think about this that I’ve found is that the “Job queue” is a queue hanging off the end of every tick in the event loop queue. Certain async-implied actions that may occur during a tick of the event loop will not cause a whole new event to be added to the event loop queue, but will instead add an item (aka Job) to the end of the current tick’s Job queue.

It’s kinda like saying, “oh, here’s this other thing I need to do later, but make sure it happens right away before anything else can happen.”

Or, to use a metaphor: the event loop queue is like an amusement park ride, where once you finish the ride, you have to go to the back of the line to ride again. But the Job queue is like finishing the ride, but then cutting in line and getting right back on.

ES6为了配合新添加的Promise机制在event loop的基础上添加了job queue的机制,而job queue就像是一个VIP队列,它里面的task永远排在event loop的当前执行的task后面,只有它当中没有task了,才会轮到event loop之后的task去执行。

Chapter 2: Callbacks

Sequential Brain

In fact, one way of simplifying (i.e., abusing) the massively complex world of neurology into something I can remotely hope to discuss here is that our brains work kinda like the event loop queue.

If you think about every single letter (or word) I type as a single async event, in just this sentence alone there are several dozen opportunities for my brain to be interrupted by some other event, such as from my senses, or even just my random thoughts.

I don’t get interrupted and pulled to another “process” at every opportunity that I could be (thankfully – or this book would never be written!). But it happens often enough that I feel my own brain is nearly constantly switching to various different contexts (aka “processes”). And that’s an awful lot like how the JS engine would probably feel.

不说还真没发觉人的大脑也是“单核”的。

The only thing worse than not knowing why some code breaks is not knowing why it worked in the first place! It’s the classic “house of cards” mentality: “it works, but not sure why, so nobody touch it!” You may have heard, “Hell is other people” (Sartre), and the programmer meme twist, “Hell is other people’s code.” I believe truly: “Hell is not understanding my own code.” And callbacks are one main culprit.

真·至理名言!不知道为什么出了问题至少还有迹可循,不知道为什么能正常工作可能想弄明白都无从下手,并且很可能因此产生更多的问题。

Trust Issues

If you have code that uses callbacks, especially but not exclusively with third-party utilities, and you’re not already applying some sort of mitigation logic for all these inversion of control trust issues, your code has bugs in it right now even though they may not have bitten you yet. Latent bugs are still bugs.

Hell indeed.

这里作者说了关于回调函数的另一个问题,难以确保你的异步回调的整个流程是正确的,尤其是当你使用了第三方的异步执行的库之后。比如说一个普通的函数,你是可以去验证它的输入类型,在输入类型不正确时可以进行适当地处理,而对于回调函数而言,你要去确保某个回调函数只被执行了一次是比较难的(比如网络请求的回调函数,请求失败可能会retry,但此时回调函数可能被重复执行了,或者一些情况下可能没有被执行,情况比较多也不容易处理)。

当然,现在我们知道JavaScript中新添加的Promise机制(每个异步回调都分了几种情况来处理)可以多多少少降低异步回调出现的这些问题了。

Chapter 3: Promises

What Is a Promise?

Let’s go back to our

x + ymath operation. Imagine if there was a way to say, “Addxandy, but if either of them isn’t ready yet, just wait until they are. Add them as soon as you can.”Your brain might have just jumped to callbacks. OK, so…

function add(getX,getY,cb) { var x, y; getX( function(xVal){ x = xVal; // both are ready? if (y != undefined) { cb( x + y ); // send along sum } } ); getY( function(yVal){ y = yVal; // both are ready? if (x != undefined) { cb( x + y ); // send along sum } } ); } // `fetchX()` and `fetchY()` are sync or async // functions add( fetchX, fetchY, function(sum){ console.log( sum ); // that was easy, huh? } );

如何实现对两个异步的函数的返回值进行相加操作,想想还是一个蛮有意思的问题呢。

Because Promises encapsulate the time-dependent state – waiting on the fulfillment or rejection of the underlying value – from the outside, the Promise itself is time-independent, and thus Promises can be composed (combined) in predictable ways regardless of the timing or outcome underneath.

Moreover, once a Promise is resolved, it stays that way forever – it becomes an immutable value at that point – and can then be observed as many times as necessary.

Promise被resolve之后是不可变的。

Thenable Duck Typing

As such, it was decided that the way to recognize a Promise (or something that behaves like a Promise) would be to define something called a “thenable” as any object or function which has a

then(..)method on it. It is assumed that any such value is a Promise-conforming thenable.

But keep in mind that there were several well-known non-Promise libraries preexisting in the community prior to ES6 that happened to already have a method on them called

then(..). Some of those libraries chose to rename their own methods to avoid collision (that sucks!). Others have simply been relegated to the unfortunate status of “incompatible with Promise-based coding” in reward for their inability to change to get out of the way.

Promise本身只是一种协议(或者叫规范)嘛,所以只要满足一定要求就是Promise。因此,要检查一个对象是否是Promise对象还蛮难的,像这里说的检查是否包含then函数属性也不完全靠谱。

Promise Trust

That is, when a Promise is resolved, all

then(..)registered callbacks on it will be called, in order, immediately at the next asynchronous opportunity (again, see “Jobs” in Chapter 1), and nothing that happens inside of one of those callbacks can affect/delay the calling of the other callbacks.For example:

p.then( function(){ p.then( function(){ console.log( "C" ); } ); console.log( "A" ); } ); p.then( function(){ console.log( "B" ); } ); // A B CHere,

"C"cannot interrupt and precede"B", by virtue of how Promises are defined to operate.

我的理解是,Promise本身会存储一个状态,当这个状态转变为“resolve”或“reject”时它会去把所有通过then函数注册进来的对应该状态的函数放到Jobs队列当中,而当一个函数通过then注册时,也会先检查该Promise的状态,若是有状态的(“resolve”或“reject”),则直接把对应的回调函数放到Jobs队列中。

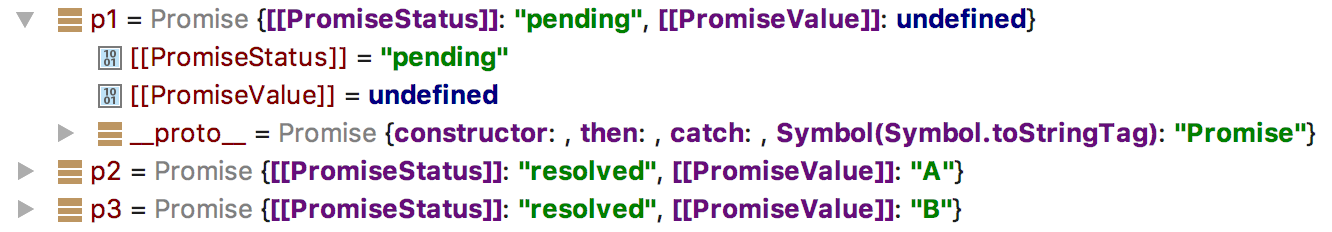

通过Webstorm查看Promise类型的对象可以看到,Promise对象除了拥有一个状态以外,还会存储一个值,这个值其实就是它本身的resolve函数或reject函数的输入的值:

而即使都是在Jobs队列当中,也是有一个先后顺序的,所以上面的例子中C会在B后面,因为A、B一开始就注册进来了,当p变成“resolve”状态时,A、B就被放到Jobs队列中了,而当A部分代码开始执行时才会将C放到Jobs队列中。

var p3 = new Promise( function(resolve,reject){ resolve( "B" ); } ); var p1 = new Promise( function(resolve,reject){ resolve( p3 ); } ); var p2 = new Promise( function(resolve,reject){ resolve( "A" ); } ); p1.then( function(v){ console.log( v ); } ); p2.then( function(v){ console.log( v ); } ); // A B <-- not B A as you might expectWe’ll cover this more later, but as you can see,

p1is resolved not with an immediate value, but with another promisep3which is itself resolved with the value"B". The specified behavior is to unwrapp3intop1, but asynchronously, sop1’s callback(s) are behindp2’s callback(s) in the asynchronous Job queue (see Chapter 1).To avoid such nuanced nightmares, you should never rely on anything about the ordering/scheduling of callbacks across Promises. In fact, a good practice is not to code in such a way where the ordering of multiple callbacks matters at all. Avoid that if you can.

这个例子按我上面的理解也能勉强解释得通。因为p3是在p1执行时才入的Jobs队列,而p1执行时p2已经在队列中了,所以p3会排到p2之后。当然,实践中最好不要有这种两个Promise之间的顺序依赖。

First, nothing (not even a JS error) can prevent a Promise from notifying you of its resolution (if it’s resolved). If you register both fulfillment and rejection callbacks for a Promise, and the Promise gets resolved, one of the two callbacks will always be called.

Promises are defined so that they can only be resolved once. If for some reason the Promise creation code tries to call

resolve(..)orreject(..)multiple times, or tries to call both, the Promise will accept only the first resolution, and will silently ignore any subsequent attempts.

也就是说Promise中先被执行的那个回调函数(resolve()或者reject())决定了Promise的状态,之后状态就不会再变了。比如reject()先执行了,那之后即使代码中还有resolve(),实际运行时也是会跳过的,即Promise在执行resolve()或reject()之前会先查看自身的状态,只有自身状态不为undefined时才会去执行(即Promise的状态只可能从undefined变为resolve或reject中的一个,不可能会从resolve变成reject或相反)。除了这两个回调函数之外的代码仍然是正常执行的。

比如:

var p4 = new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

resolve("D");

console.log("E");

reject("F"); // ignored cause p4 already has resolve status

console.log("G");

});

p4.then(function (v) {

console.log(v);

});

// E G D

Something to be aware of: If you call

resolve(..)orreject(..)with multiple parameters, all subsequent parameters beyond the first will be silently ignored. Although that might seem a violation of the guarantee we just described, it’s not exactly, because it constitutes an invalid usage of the Promise mechanism. Other invalid usages of the API (such as callingresolve(..)multiple times) are similarly protected, so the Promise behavior here is consistent (if not a tiny bit frustrating).If you want to pass along multiple values, you must wrap them in another single value that you pass, such as an

arrayor anobject.

又一个关于Promise的规则:resolve或reject回调只能有一个输入参数。

If at any point in the creation of a Promise, or in the observation of its resolution, a JS exception error occurs, such as a

TypeErrororReferenceError, that exception will be caught, and it will force the Promise in question to become rejected.For example:

var p = new Promise( function(resolve,reject){ foo.bar(); // `foo` is not defined, so error! resolve( 42 ); // never gets here :( } ); p.then( function fulfilled(){ // never gets here :( }, function rejected(err){ // `err` will be a `TypeError` exception object // from the `foo.bar()` line. } );The JS exception that occurs from

foo.bar()becomes a Promise rejection that you can catch and respond to.This is an important detail, because it effectively solves another potential Zalgo moment, which is that errors could create a synchronous reaction whereas nonerrors would be asynchronous. Promises turn even JS exceptions into asynchronous behavior, thereby reducing the race condition chances greatly.

Promise中在resolve之前抛出异常会导致Promise状态变为“reject”,并且对应的reject回调函数会接住这个异常。如果异常是在Promise状态变为“resolve”之后抛出的呢?这个异常会被忽视(这一点感觉不太合理,要debug这种情况简直要哭啊):

var p6 = new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

resolve("p6 resolved");

f.bar();// `f` is not defined, but the promise is resolved and its status will not change. So the error is ignored!

console.log('---p6---') // never gets here as error happens before

});

p6.then(

function fulfilled(v) {

console.log(v);

},

function rejected(err) {

console.log(err); // never gets here

}

);

异常导致的“reject”和主动执行reject()的一个区别就是,reject()之后的(除了resolve()和reject())代码仍然会正常执行,而异常点之后的代码则不会再执行了。

If you pass an immediate, non-Promise, non-thenable value to

Promise.resolve(..), you get a promise that’s fulfilled with that value. In other words, these two promisesp1andp2will behave basically identically:var p1 = new Promise( function(resolve,reject){ resolve( 42 ); } ); var p2 = Promise.resolve( 42 );But if you pass a genuine Promise to

Promise.resolve(..), you just get the same promise back:var p1 = Promise.resolve( 42 ); var p2 = Promise.resolve( p1 ); p1 === p2; // true

var p = { then: function(cb,errcb) { cb( 42 ); errcb( "evil laugh" ); } }; p .then( function fulfilled(val){ console.log( val ); // 42 }, function rejected(err){ // oops, shouldn't have run console.log( err ); // evil laugh } );This

pis a thenable but it’s not so well behaved of a promise. Is it malicious? Or is it just ignorant of how Promises should work? It doesn’t really matter, to be honest. In either case, it’s not trustable as is.Nonetheless, we can pass either of these versions of

ptoPromise.resolve(..), and we’ll get the normalized, safe result we’d expect:Promise.resolve( p ) .then( function fulfilled(val){ console.log( val ); // 42 }, function rejected(err){ // never gets here } );Promise.resolve(..) will accept any thenable, and will unwrap it to its non-thenable value. But you get back from Promise.resolve(..) a real, genuine Promise in its place, one that you can trust. If what you passed in is already a genuine Promise, you just get it right back, so there’s no downside at all to filtering through Promise.resolve(..) to gain trust.

通过Promise.resolve(..)函数可以将传入的对象转变成一个resolve状态的Promise对象,无论这个对象原来是不是Promise对象,或者它只是一个具有then属性的鸭子类型的对象。因此,当我们不确定一个对象是否是Promise对象但又希望把它作为Promise对象来处理时,可以先使用Promise.resolve来处理一下该对象。类似的,Promise.reject(..)函数可以将输入的对象转变为一个reject状态的Promise对象。

Chain Flow

- Every time you call

then(..)on a Promise, it creates and returns a new Promise, which we can chain with.- Whatever value you return from the

then(..)call’s fulfillment callback (the first parameter) is automatically set as the fulfillment of the chained Promise (from the first point).Let’s first illustrate what that means, and then we’ll derive how that helps us create async sequences of flow control. Consider the following:

var p = Promise.resolve( 21 ); var p2 = p.then( function(v){ console.log( v ); // 21 // fulfill `p2` with value `42` return v * 2; } ); // chain off `p2` p2.then( function(v){ console.log( v ); // 42 } );

Promise对象的then函数会创建(返回)另一个Promise对象(它接收两个函数作为参数,分别为resolve和reject函数),并且Promise对象的状态决定了该对象的then函数中是resolve函数被调用还是reject函数被调用,且Promise对象的状态值决定了then函数中被调用的输入。

需要注意的是,Promise定义时是接收一个函数作为参数的,而该函数接收了两个回调函数分别为resolve和reject函数。可以理解为then函数就是Promise定义时接收的那个函数:

function then(resolve, reject) {

// Do something according to the status of last Promise

// For example, like below codes:

if (this.status === 'resolved') {

return Promise.resolve(resolve(this.value));

}

else {

return Promise.resolve(reject(this.value));

}

}

var p = new Promise(then);

Even though we wrapped

42up in a promise that we returned, it still got unwrapped and ended up as the resolution of the chained promise, such that the secondthen(..)still received42. If we introduce asynchrony to that wrapping promise, everything still nicely works the same:var p = Promise.resolve( 21 ); p.then( function(v){ console.log( v ); // 21 // create a promise to return return new Promise( function(resolve,reject){ // introduce asynchrony! setTimeout( function(){ // fulfill with value `42` resolve( v * 2 ); }, 100 ); } ); } ) .then( function(v){ // runs after the 100ms delay in the previous step console.log( v ); // 42 } );That’s incredibly powerful! Now we can construct a sequence of however many async steps we want, and each step can delay the next step (or not!), as necessary.

正如我上面所猜想的一样,then函数返回时会用Promise.resolve包装一下来确保返回的是一个Promise对象。当Promise对象的状态变为resolve或reject时才会调用then函数,所以可以串起异步的操作。

If a proper valid function is not passed as the fulfillment handler parameter to

then(..), there’s also a default handler substituted:var p = Promise.resolve( 42 ); p.then( // assumed fulfillment handler, if omitted or // any other non-function value passed // function(v) { // return v; // } null, function rejected(err){ // never gets here } );As you can see, the default fulfillment handler simply passes whatever value it receives along to the next step (Promise).

Note: The

then(null,function(err){ .. })pattern – only handling rejections (if any) but letting fulfillments pass through – has a shortcut in the API:catch(function(err){ .. }).

then函数的输入如果不是一个函数,Promise会使用一个默认的handler函数来处理,即把resolve(reject)的值原封不动地返回到下一层。

catch(rejectCallback)函数相当于then(null,rejectCallback),即只处理reject状态的then函数。

Error Handling

try..catchwould certainly be nice to have, but it doesn’t work across async operations. That is, unless there’s some additional environmental support, which we’ll come back to with generators in Chapter 4.In callbacks, some standards have emerged for patterned error handling, most notably the “error-first callback” style:

function foo(cb) { setTimeout( function(){ try { var x = baz.bar(); cb( null, x ); // success! } catch (err) { cb( err ); } }, 100 ); } foo( function(err,val){ if (err) { console.error( err ); // bummer :( } else { console.log( val ); } } );

Go语言好像就是建议这么做的,函数第一个输入默认为error,不过也是被人诟病比较多的一个特性。

Promises don’t use the popular “error-first callback” design style, but instead use “split callbacks” style; there’s one callback for fulfillment and one for rejection.

While this pattern of error handling makes fine sense on the surface, the nuances of Promise error handling are often a fair bit more difficult to fully grasp.

Consider:

var p = Promise.resolve( 42 ); p.then( function fulfilled(msg){ // numbers don't have string functions, // so will throw an error console.log( msg.toLowerCase() ); }, function rejected(err){ // never gets here } );

Jeff Atwood noted years ago: programming languages are often set up in such a way that by default, developers fall into the “pit of despair” (http://blog.codinghorror.com/falling-into-the-pit-of-success/) – where accidents are punished – and that you have to try harder to get it right. He implored us to instead create a “pit of success,” where by default you fall into expected (successful) action, and thus would have to try hard to fail.

Promise error handling is unquestionably “pit of despair” design. By default, it assumes that you want any error to be swallowed by the Promise state, and if you forget to observe that state, the error silently languishes/dies in obscurity – usually despair.

这里说的是uncaught exception的问题,即如果我忘记去处理Promise中产生的error了,或处理error的函数中又产生新的error了,这些情况都没有在Promise的设计中考虑到。

要解决上面这类问题,就是要把这些error能像正常程序的出现的异常一样抛出来,而不是傻傻地指望有代码去处理(这样异常就被吞了)。这在Promise刚出来时确实是一个大问题,但现在我在在NodeJS (v8.5.0)环境中尝试了下是可以正确地抛出UnhandledPromiseRejectionWarning的全局异常的。

Promise Patterns

Say you wanted to make two Ajax requests at the same time, and wait for both to finish, regardless of their order, before making a third Ajax request. Consider:

// `request(..)` is a Promise-aware Ajax utility, // like we defined earlier in the chapter var p1 = request( "http://some.url.1/" ); var p2 = request( "http://some.url.2/" ); Promise.all( [p1,p2] ) .then( function(msgs){ // both `p1` and `p2` fulfill and pass in // their messages here return request( "http://some.url.3/?v=" + msgs.join(",") ); } ) .then( function(msg){ console.log( msg ); } );

Promise.all([ .. ])expects a single argument, anarray, consisting generally of Promise instances. The promise returned from thePromise.all([ .. ])call will receive a fulfillment message (msgsin this snippet) that is anarrayof all the fulfillment messages from the passed in promises, in the same order as specified (regardless of fulfillment order).

Promise.all([ .. ])会创建一个新的Promise对象,它在所有输入的Promise对象状态全部变为resolve时才会变成resolve状态,但只要有某个输入的Promise对象状态为reject了,它也会立刻变为reject的状态(即使其他输入的Promise对象还没有出状态)。这就有点像是逻辑操作中的“与”操作,只要有一个输入是false,其他的输入也就不用管了,结果就是false。

Similar to

Promise.all([ .. ]),Promise.race([ .. ])will fulfill if and when any Promise resolution is a fulfillment, and it will reject if and when any Promise resolution is a rejection.// `request(..)` is a Promise-aware Ajax utility, // like we defined earlier in the chapter var p1 = request( "http://some.url.1/" ); var p2 = request( "http://some.url.2/" ); Promise.race( [p1,p2] ) .then( function(msg){ // either `p1` or `p2` will win the race return request( "http://some.url.3/?v=" + msg ); } ) .then( function(msg){ console.log( msg ); } );Because only one promise wins, the fulfillment value is a single message, not an

arrayas it was forPromise.all([ .. ]).

Promise.race([ .. ])同样会创建一个新的Promise对象,它会和所有输入的Promise对象中第一个达到resolve状态或reject状态的对象同时(更准确地说是紧随其后)变为与之相同的状态,其他的输入对象就不管了。

While native ES6 Promises come with built-in

Promise.all([ .. ])andPromise.race([ .. ]), there are several other commonly used patterns with variations on those semantics:

none([ .. ])is likeall([ .. ]), but fulfillments and rejections are transposed. All Promises need to be rejected – rejections become the fulfillment values and vice versa.any([ .. ])is likeall([ .. ]), but it ignores any rejections, so only one needs to fulfill instead of all of them.first([ .. ])is like a race withany([ .. ]), which is that it ignores any rejections and fulfills as soon as the first Promise fulfills.last([ .. ])is likefirst([ .. ]), but only the latest fulfillment wins.Some Promise abstraction libraries provide these, but you could also define them yourself using the mechanics of Promises,

race([ .. ])andall([ .. ]).For example, here’s how we could define

first([ .. ]):// polyfill-safe guard check if (!Promise.first) { Promise.first = function(prs) { return new Promise( function(resolve,reject){ // loop through all promises prs.forEach( function(pr){ // normalize the value Promise.resolve( pr ) // whichever one fulfills first wins, and // gets to resolve the main promise .then( resolve ); } ); } ); }; }

这里first([ .. ])的实现利用了Promise的一个特性:即Promise对象的状态一旦变为了非undefined的值就不会再变化了,即Promise对象是immutable的。这里就只有第一个调用的resolve函数是有效的,后续的调用已经对返回的Promise对象没有影响了。

For example, let’s consider an asynchronous

map(..)utility that takes anarrayof values (could be Promises or anything else), plus a function (task) to perform against each.map(..)itself returns a promise whose fulfillment value is anarraythat holds (in the same mapping order) the async fulfillment value from each task:if (!Promise.map) { Promise.map = function(vals,cb) { // new promise that waits for all mapped promises return Promise.all( // note: regular array `map(..)`, turns // the array of values into an array of // promises vals.map( function(val){ // replace `val` with a new promise that // resolves after `val` is async mapped return new Promise( function(resolve){ cb( val, resolve ); } ); } ) ); }; }

这里vals是一组Promise对象,cb是一个回调函数,接收一个Promise对象和它的resolve函数。

Comments